Allen and I travelled north for our break to spend time with our children and grandchildren. The parents among you will appreciate that this entails a degree of work as two of the children were moving house and so some packing and heavy lifting were required. The highlight was the First Holy Communion of two of our grandsons, Jack and Angus. This was very much a big family day with Jack and Angus taking up positions to sit close to Allen and me. I certainly sensed their feeling of now being a ‘grown up’ person in the church, at the ages of eight and nine. It was good to have about twenty of us there to mark this occasion and to celebrate.

Allen and I travelled north for our break to spend time with our children and grandchildren. The parents among you will appreciate that this entails a degree of work as two of the children were moving house and so some packing and heavy lifting were required. The highlight was the First Holy Communion of two of our grandsons, Jack and Angus. This was very much a big family day with Jack and Angus taking up positions to sit close to Allen and me. I certainly sensed their feeling of now being a ‘grown up’ person in the church, at the ages of eight and nine. It was good to have about twenty of us there to mark this occasion and to celebrate.

Most immediately to writing this message, I attended the Tenison Woods Education Centre (TWEC) dinner on Friday night, at which Professor the Honourable Dame Marie Bashir spoke on leadership. You may recall that she was Governor of NSW from 2001 to 2014.  While she spoke well on leadership, it was who she was, in person, that spoke powerfully to me of leadership. She is an authentic person who is proud of her heritage and seems to have used all her gifts and experiences for the good of many. Her gentle way and her desire to engage with people are part of who she is and clearly she believes that faith and education are essential elements to a good life. At the age of 85, she was very impressive and an outstanding role model for women and men. It was an honour to meet her and to listen to her story. I believe leadership requires us to become the person we were created to be, and then to accept that person as individually different from anyone else who has been created. Love of God, self, others and creation are at the essence of being good and doing good. It is clearly a mystery and when I view the photo of my eleven brothers and sisters, born of the same parents and growing up in the same household, I am in awe of the mystery of even those from the same gene pool having a diverse variety of gifts and talents. Listening to Marie Bashir instilled even further in me the great gift and responsibility of parenting and family. All those in leadership have been primarily formed by their first families and this is what instils in them the values from which they lead.

While she spoke well on leadership, it was who she was, in person, that spoke powerfully to me of leadership. She is an authentic person who is proud of her heritage and seems to have used all her gifts and experiences for the good of many. Her gentle way and her desire to engage with people are part of who she is and clearly she believes that faith and education are essential elements to a good life. At the age of 85, she was very impressive and an outstanding role model for women and men. It was an honour to meet her and to listen to her story. I believe leadership requires us to become the person we were created to be, and then to accept that person as individually different from anyone else who has been created. Love of God, self, others and creation are at the essence of being good and doing good. It is clearly a mystery and when I view the photo of my eleven brothers and sisters, born of the same parents and growing up in the same household, I am in awe of the mystery of even those from the same gene pool having a diverse variety of gifts and talents. Listening to Marie Bashir instilled even further in me the great gift and responsibility of parenting and family. All those in leadership have been primarily formed by their first families and this is what instils in them the values from which they lead.

I am sure you are still suffering from last week’s atrocity in America. Like many of you I read some articles on this during the week and I would like to share with you some of the words that spoke to me.

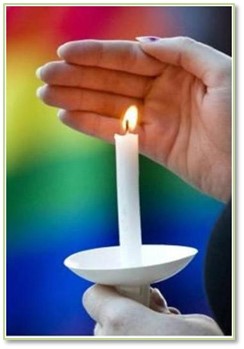

The Newcastle Herald featured a column, written by Billy Kluttz, the evening services co-ordinator at Immanuel Presbyterian Church in Virginia, Why I light candles after a tragedy like the Orlando mass shooting, on June 14.

We want policy change, not prayers." Immediately following the violence in Orlando, my friends' social media posts made their priorities clear. They were unimpressed with the deluge of social media piety following the latest mass shooting.

As a gay man, I heard their plea: They saw prayer-themed hashtags and photos as nothing more than unwanted trifle. But as a Christian, following the horrific news on Sunday morning, I did what people of faith do best: I lit candles. A few others sent out tweets, we showed up to vigils and we lit more candles.

Our religious rituals are a spiritual emergency preparedness plan of sorts. We practise the fire drills so that when the panic of actual smoke and flame overtake us, we will hopefully remember where the exit is - or at least which direction to crawl.

Sunday's attack left me disoriented. Amid confusion, I revert to the spiritual version of stop, drop and roll. I do the only thing I can remember how to do. I light candles. I say prayers. I trust the process: Somehow the ritual will reorient me, ground me.

As useless as this seems, it works. Or it will work, in time. Rituals sustain us past the trauma; they remind us to breathe. For queer people of faith, rituals help us survive - because the next, most logical step isn't always clear. There isn't always a singular policy solution for the complex global intersections of religion, sexuality, gender and violence.

And so, I continue the useless practice of lighting candles. And I stand there beside others lost in the senselessness and sadness.

As the candles burn out, the uselessness of it all is most apparent. My friends were right; our candles have done nothing. The loss is just as real. But somehow, we have acknowledged the loss, and somehow, we have found our foothold, together.

I found these words to be quite consoling. It is six months since our granddaughter, Ada, passed away and the many ongoing practicalities of dealing with this loss are made more bearable because we have ritualised this passing and continue to work towards a way to remember, that marks the life of this little person without, in the words of our daughter, ‘setting up a shrine’. We need ways to mark happy occasions and sad events. Symbols are so important to either process. (Just a reminder that it is Red Nose Day this Friday 24th June for those who might like to donate to SIDS research.)

Michael Jensen, the rector of St Mark’s Anglican Church, Darling Point, wrote a good article on the ABC Religion and Ethics page on June 15 – The Orlando Tragedy: What Can be Said?

He speaks of our need as humans to wish to narrate the story into moral meaningfulness, the reason is self-evident. Many have given the event and the killer a narrative of terror. Jensen says that “we want his horror to fit into our story-telling because to tell the story gives us a measure of control and understandin”. He goes onto say:

But what we need most is not declaration of the undoubted meaning of the catastrophe, but lament. We need not commentary, but poetry.

The causes of this kind of calamity lie not simply with a lack of the adequate laws, or with the blaming of this or that group. What hidden rage could possibly cause an individual to murder without compassion or sorrow fifty of his fellow creatures? It cannot be reduced to one simple strand. It is, like most evil, absurd.

We want to generalise - to read the event in the light of cultural themes that are familiar to us - when what happened is filled with hideous and strange particularities.

What the word "tragedy" allows us to do is to sit in the dust bewildered at what has happened; to recognise that others are in agony, and that as human beings, we have been spared that agony not because we are virtuous, but because - this time - our group wasn't in the frame.

The sixteenth century poet Sir Phillip Sidney wrote of tragedy that it

teacheth the uncertainety of this world, and upon how weake foundations guilden roofes are builded.

That is true of dramatic tragedy, and also of the real life incidents we rightly name tragedy, too. This sense of uncertainty taught us in tragedy leads to the twinned emotions of pity and fear - pity for those who suffer, and fear that we might share their fate.

Could these emotions in the end prove more constructive than the outrage that burns away our emotional circuitry day after day? That anger is righteous, but it has no place to go. But pity, or pathos, builds to sym-pathy, and com-passion; and fear builds to humility and respect for life's preciousness and fragility, and a seeking after that which transcends us.

So during this week, when we contemplate the gospel reading from Luke (9:18-24) where Jesus asks his disciples, “Who do you say I am?”, a question which he continues to ask of us daily, we might consider our lament for what is and what could be. We are asked to be clothed in Christ, to be one body. And how amazingly spectacular was the Psalm (62) for the weekend. “My soul is thirsting for you, O Lord my God”. I have no doubt that this psalmist is correct in placing upon humans the longing they have for seeking God –

O God, you are my God, for you I long;

for you my soul is thirsting.

My body pines for you

like a dry, weary land without water.

So here I am back with you pondering the great mystery we call life, and happy to be journeying with you.